By necessity this section is kinda skimpy, mainly because I don’t really do non-fiction. That said, One Magazine presented me with a great opportunity this year to test my journalistic mettle. Martin Belk, editor and cofounder of One Magazine invited me to Prague to help the mag cover The 2008 Prague Writers’ Festival. I have to confess, I was a little intimidated by the prospect, reluctant even, but in the end thought what the Hell, you gotta push your boundaries every now and then, so I agreed to go along.

I won’t recount all the madcap goings on during that blisterngly hot week, but I will say that is was both humbling and fascinating, and something I’m so glad I agreed to do. You can read all about One Magazine’s experiences at The 2008 Prague Writers’ Festival on the One Magazine site (including some of the interviews I conducuted).

I wrote a feature article for the 5th edition of the magazine. It was edited, naturally, for space, but as this is my own site, I thought I’d post the article in full.

Title: Entropy Rising

Word count: 3,400

1968 was a momentous year by any standards, a year of political turmoil and social revolution. In Mexico City hundreds of unarmed protestors were fired upon by Government troops, a little-know Iraqi soldier took part in a military coup which would eventually catapult him to the presidency, Warsaw Pact tanks rolled into Prague quashing its nascent Spring, the Pope condemned birth control, France ground to a three week halt, and in the hamlet of Mai Lai in South Vietnam US marines slaughtered hundreds of innocent civilians. In the US itself Martin Luther King was murdered, Lyndon B Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, protesting students took over Columbia University, and another Kennedy took a bullet. The world boiled.

1968 was a momentous year by any standards, a year of political turmoil and social revolution. In Mexico City hundreds of unarmed protestors were fired upon by Government troops, a little-know Iraqi soldier took part in a military coup which would eventually catapult him to the presidency, Warsaw Pact tanks rolled into Prague quashing its nascent Spring, the Pope condemned birth control, France ground to a three week halt, and in the hamlet of Mai Lai in South Vietnam US marines slaughtered hundreds of innocent civilians. In the US itself Martin Luther King was murdered, Lyndon B Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, protesting students took over Columbia University, and another Kennedy took a bullet. The world boiled.

Simultaneously it was a time of artistic and cultural ferment. In that year the Beatles released the White Album, Andy Warhol painted a tin of soup, Kubrik made a monkey out of us in 2001, and the first Big Mac was served in Pittsburgh. A time of alchemy.

It’s in this context that I’d like to talk about things that at first might appear unrelated, disparate, disjointed even. I’d like to focus on two countries – countries that for reasons that will soon become apparent are where my interest in the cultural and political legacy of 1968 lie – and two of their native artists. Of the two countries, one was at the epicentre of the pop culture revolution, and the other at the vanguard of the struggle for a new kind of human socialism. Both are close to my heart. The first because I live there (Britain – or Scotland, Britain isn’t technically a country), and the second because I seem to keep being drawn back there. Mind you, my return visits to the Czech Republic (and inevitably, Prague) could easily be attributed to my inability NOT to rub the brass relief of the statue of St John of Nepomuk on The Charles Bridge (according to legend if you rub the statue you’ll return one day). I should add that of course this time I rubbed it again (a man never tires of rubbing) so this might not be the last I have to say on the matter. The two artists are British novelist David Britton, and the renowned Czech animator, Jan Svankmajer. More of this unlikely pair later.

My journey begins in Kutna Hora, once the second most wealthy and important town in Bohemia. Well actually it starts in Prague’s railway station, Praha Hlavni Nadrazi, at half eight in the morning, but Kutna Hora is where I’m going. I’m in Prague with One Magazine to cover the 2008 Prague Writers’ Festival, appropriately themed around 1968 and the Prague Spring. This is my special assignment and I’m waiting on my colleague and photographer for the day, the charming Thomas Haywood. I buy our tickets and it’s not long before we’re trundling through the lush Czech countryside in our quaint wee cabin. Thomas is trying to educate me about camera speeds, light meters, and various pentaxian arcana. I follow most of it but keep getting drawn back to the delirious riot of green beyond the window, like a Leprechaun returning to his spew.

My journey begins in Kutna Hora, once the second most wealthy and important town in Bohemia. Well actually it starts in Prague’s railway station, Praha Hlavni Nadrazi, at half eight in the morning, but Kutna Hora is where I’m going. I’m in Prague with One Magazine to cover the 2008 Prague Writers’ Festival, appropriately themed around 1968 and the Prague Spring. This is my special assignment and I’m waiting on my colleague and photographer for the day, the charming Thomas Haywood. I buy our tickets and it’s not long before we’re trundling through the lush Czech countryside in our quaint wee cabin. Thomas is trying to educate me about camera speeds, light meters, and various pentaxian arcana. I follow most of it but keep getting drawn back to the delirious riot of green beyond the window, like a Leprechaun returning to his spew.

In Kutna Hora, Thomas takes a picture or two of the town plan (cunning), and I stifle a snigger at The Church of Our Lady of The Assumption. Kotnice is actually quite a small church, not much bigger the Roslyn Chapel, and unremarkable from the outside. You’d never imagine you could fit 70,000 people in it. You could, however, if you piled their bones into six gigantic pyramids, decorated the rafters with rows upon rows of leering skulls, made crucifix and giants’ goblets from them, and crafted a monstrous chandelier that reputedly contains every bone in the human body. Kotnice is the largest, and possibly the oddest, ossuary in the world. As early as 1142 there was a Cistercian monastery here, and in 1278 the abbot of Sedlec (a small village and now a suburb of Kutna Hora) returned from a trip to the Holy Land with some soil he’d collected at Calvary. Being a religious sort he sprinkled the soil over the cemetery. Word got round and you know how it is, people just couldn’t wait to be buried there. The dead came in their droves from all around Europe. Very quickly it started to get a little crowded. An overcrowding that was exacerbated by the bubonic plague. In 1318 there were about 30,000 people buried in the cemetery. Next the Hussite wars of the 15th century swelled the numbers even more. The ground positively groaned with the dead. Before long a church was built and the remains were stored in its cellar as the graveyard was cleared of old graves and rapidly reused. Something had to be done. A half blind Cistercian monk then began arranging the stacked bones in to six huge pyramids. The final configuration of the ossuary, including its bizarre sculptures, was the work of wood carver František Rint, who with the help of his family, created the decor for which Kotnice would become famous. It took him ten years and was completed in 1870. He was even kind enough to sign his work in bones near the entrance. How’s that for a statement on the futility and vanity of the artist? He probably just thought it looked cool.

As Thomas and I arrive parties of school kids are being ushered in and out to a regular rhythm of laughter, shoves and teacherly admonishings. We decide to sit it out for a bit and enjoy the sunshine. In a rare break in the maelstrom, we seize our chance and duck inside, paying a relaxed looking student manning the door. My first impressions are naturally of the sheers scale and bizarre artistry of it all. Teetering columns of skulls and crossed bones snake up the walls, and unidentifiable spinal bits weave sinuously across the arches and ceiling. A row of skulls directly above the entrance watches in silent contemplation as one party of visitors after another assemble beneath their hollowed gaze. I can’t help but wonder what the heads talk about when the caretaker has finally left for the night, killing the spot lights and leaving them to the semi-eternal darkness and silence? But stop me before I wax too melancholic. This is no sepulchral, doom-laden tomb. Besides, none of the said skulls have bottom jaws. My immediate impression, other than the obvious awe, is one quite hope filled, warm even. These skulls, bones and skeletons seem to be enjoying the spectacle. There a few mere mortals that can expect to have their grave visited day in day out for hundreds of years. No slow dissolution for these lucky souls. They get to see social history unfold before their perpetually grinning faces. Some of the vainer (or venerable) inhabitants have acquired a patina or gray dust on their once bare skulls, a desperate attempt to rejoin the ranks of the living or just indicative of the impracticalities of dusting the place? Perhaps it’s the sun beating through the low windows and slicing across plaster, tile and bone, or perhaps it’s the laughter of children outside or the ever-present bird song, but this is nothing like I’d expected. Your average Goth would be sorely disappointed. It does smell of earth, damp and some other unidentified calcified odour, which is some consolation.

As Thomas and I arrive parties of school kids are being ushered in and out to a regular rhythm of laughter, shoves and teacherly admonishings. We decide to sit it out for a bit and enjoy the sunshine. In a rare break in the maelstrom, we seize our chance and duck inside, paying a relaxed looking student manning the door. My first impressions are naturally of the sheers scale and bizarre artistry of it all. Teetering columns of skulls and crossed bones snake up the walls, and unidentifiable spinal bits weave sinuously across the arches and ceiling. A row of skulls directly above the entrance watches in silent contemplation as one party of visitors after another assemble beneath their hollowed gaze. I can’t help but wonder what the heads talk about when the caretaker has finally left for the night, killing the spot lights and leaving them to the semi-eternal darkness and silence? But stop me before I wax too melancholic. This is no sepulchral, doom-laden tomb. Besides, none of the said skulls have bottom jaws. My immediate impression, other than the obvious awe, is one quite hope filled, warm even. These skulls, bones and skeletons seem to be enjoying the spectacle. There a few mere mortals that can expect to have their grave visited day in day out for hundreds of years. No slow dissolution for these lucky souls. They get to see social history unfold before their perpetually grinning faces. Some of the vainer (or venerable) inhabitants have acquired a patina or gray dust on their once bare skulls, a desperate attempt to rejoin the ranks of the living or just indicative of the impracticalities of dusting the place? Perhaps it’s the sun beating through the low windows and slicing across plaster, tile and bone, or perhaps it’s the laughter of children outside or the ever-present bird song, but this is nothing like I’d expected. Your average Goth would be sorely disappointed. It does smell of earth, damp and some other unidentified calcified odour, which is some consolation.

Perhaps Svankmajer is to blame for my unexpected sense of serenity? I’ve always enjoyed stop animation. I like regular two-dimensional cartoons too, and even a bit of computer animation, but stop animation can be at once both frightening and hugely heart warming. There’s something alchemical about it. In the hands of the stop animator anything can be given life. Objects have their own agendas, are imbued with their own thoughts, given their own worlds. It’s an expansive, subversive medium. You just never know what to expect. There’s something at once compelling, but at the same time slightly sinister. Like a good fairytale. Maybe it’s something to do with growing up? Stop animation featured in every monster film I ever hid from and was the mainstay of children’s programming throughout my formative years. I can’t help but love it.

Jan Svankmajer may not be as famous as Ray Harryhausen, but his legacy as one of Europe’s most revered stop-animators is beyond dispute. Not that Svankmajer would necessarily identify himself as an animator. Even though it’s undoubtedly for his animation and film work that he is best known, Svankmajer’s talents and interests stretch much further. A surrealist by admission, Svankmajer is also a prolific artist, sculptor and writer. He considers his films and animations very much as simply another aspect of his obsessive dialogue with the object and the life of things.

Jan Svankmajer was born in Prague in 1934 and trained at The Institute of Artistic Industry and the The Fine Arts Academy. This led him (somewhat naturally in Bohemia) to the theatre, and thence to film. Svankmajer’s first film was The Last trick (1964), a darkly comic tale of two mannequins desperately trying to outdo each other by disgorging strange artefacts from their heads. It was to set the tone of many of Svankmajer’s future shorts – the macabre, the poetic, the darkly comic and the vicariously surreal. Subsequent films followed: J S Bach – fantasy in G minor (1965), A game with stones (1965), Punch and Judy (1966), Et cetera (1966), Historia naturae suita (1967), The garden (1968) and The flat (1968), Picnic with Weissmann (1968), A quiet week in the house (1969), Don Juan (1969), and a film I’d like to look at in a little more detail, The ossuary (1970).

The ossuary was released a mere two years after a Soviet led Warsaw Pact invasion force crushed Czechoslovakia’s dreams of reform, or as Alexander Dubcek put it, ‘Socialism with a human face’. Dubcek was elected leader of the KSC (The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia) on the strength of his reformist policies. These included lifting restrictions on foreign travel, liberalising the arts and the media, and allowing limited forms of private enterprise and capital. Naturally he was at pains to reassure his Soviet masters that these reforms in no way weakened Czechoslovakia’s commitment to Marxist-Leninist principles. He also federalized the country into two republics.

The ossuary was released a mere two years after a Soviet led Warsaw Pact invasion force crushed Czechoslovakia’s dreams of reform, or as Alexander Dubcek put it, ‘Socialism with a human face’. Dubcek was elected leader of the KSC (The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia) on the strength of his reformist policies. These included lifting restrictions on foreign travel, liberalising the arts and the media, and allowing limited forms of private enterprise and capital. Naturally he was at pains to reassure his Soviet masters that these reforms in no way weakened Czechoslovakia’s commitment to Marxist-Leninist principles. He also federalized the country into two republics.

After a brief trip to the Kremlin and a series of failing negotiations, the Soviets led a coalition of Warsaw Pact forces into Czechoslovakia and nipped the Prague Spring in the bud. During the attack, seventy two civilians were killed, two hundred and sixty six severely wounded and another four hundred and thirty six were injured. Alexander Dubcek urged people not to resist. Within days the country was firmly back in Soviet hands. Dubcek was replaced and a vigorous pruning commenced. The freedoms Czechs had paid so dearly for were mercilessly repealed. It was in this atmosphere that Jan Svankmajer took his small crew to Kutna Hora, and Kotnice.

Svankmajer’s ossuary is a breakneck, harrowing kind of film. Shot entirely in black and white, the stasis and immobility of the ossuary is juxtaposed with insanely fast jump cuts, speeding from one scene to the next, from horrifying close up to panorama or swaying lens and back again in the blink of an eye. It is filming for the MTV generation twenty years ahead of its time. But it was for the soundtrack that Svankmajer ran into trouble. The original print of the film was accompanied by the voice of a real-life guide showing a bunch of unruly schoolchildren around. Throughout the film she constantly berates them and threatens them with a 50Kc fine should any of them touch the bones. Inevitably one of them does, and she flies off the handle demanding money, but soon segues back into her matronly-like role and standard tourist spiel. She can’t help but have a moan about stupid boys scribbling on the skulls, though, and how much trouble it is to remove the ink. Svankmajer playfully allows a quick glimpse of a doodle sporting cranium. In a strangely enigmatic slice of synchronicity, the guide goes on to explain how, in 1968, an American had offered Kotnice $100,000 for the chandelier to go to the states. Infuriatingly she doesn‘t tell us what their response was, but one can assume it was a firm Ano! as the imposing lighting fixture still dominates the centre of the ossuary.

The authorities took a dim view of the film’s satirical undertones. Perhaps they thought Svankmajer was equating the guide with the new regime, stifling the ‘children’s’ creativity and providing them with a heavily policed and stifling artistic environment? Whatever the reason, he was forced to replace the original soundtrack with a version of Jaques Prevert’s poem Comment dessiner le portrait d’un oiseau. Effective enough in its own way but by no means as satisfying as the original. Following this run in with officialdom, Svankmajer completed two more films, Jabberwocky (1971) and Leonardo’s diary (1972) before falling out of favour and abandoning film for a time to concentrate on tactile art. He didn’t return to film until 1979. Svankmajer still lives in Prague (a city Andre Breton called ‘the magical capital of Europe’) and is making films to this day.

In the wake of 1989’s Velvet Revolution, Svankmajer’s work became readily available in the west and, naturally, a version of The Ossuary was released with its original soundtrack reinstated. It’s gratifying to see Prague reclaiming its bohemian credentials. The arts are positively flourishing again in the Czech Republic and the ghost of state censorship is finally being exorcised from cultural life. Somewhat ironically, it’s this liberalisation in the Czech Republic that serves to contrast the oppressive and draconian hand of the censor in a country one would assume would be free from such state meddling, the UK.

The UK Obscene Publications Act of 1959 states that:

“[A]n article shall be deemed to be obscene if its effect or (where the article comprises two or more distinct items) the effect of any one of its items is, if taken as a whole, such as to tend to deprave and corrupt persons who are likely, having regard to all relevant circumstances, to read, see or hear the matter contained or embodied in it.”

Initially intend to combat pornographers, the act was never-the-less utilised by zealous prosecutors to combat what they saw as immorality in the arts. In 1968, the same year The Naked Lunch was first published in the UK, Selby’s Last exit to Brooklyn was banned in an English Court (this was repealed a year later). However, a precedent had been set that would find its most voluble incarnation in the Oz trials of 1971, where John Lennon and Yoko Ono, John Peel, Marty Feldman and a host of other celebrities rallied to the magazine’s cause. You’d be forgiven for thinking surely this was the last great clash of culture and state and that in these enlightened times, one is free to read and watch whatever one likes. After all, you can even see the raft of so-called ‘video-nasties’ that were for a number of years banned in this country. It may come as a surprise to many readers then to learn that the Obscene Publications Act was dusted off and wielded again, as recently as 1991 against David Britton’s novel, Lord Horror published by Savoy books. Lord Horror was the last book in the UK to be prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act. Copies of the book were seized (with some zeal at the hands of the then Chief Constable of Manchester Police James Anderton, the self-confessed God’s cop) and ordered destroyed. Britton was sentenced to four months in Strangeways.

Initially intend to combat pornographers, the act was never-the-less utilised by zealous prosecutors to combat what they saw as immorality in the arts. In 1968, the same year The Naked Lunch was first published in the UK, Selby’s Last exit to Brooklyn was banned in an English Court (this was repealed a year later). However, a precedent had been set that would find its most voluble incarnation in the Oz trials of 1971, where John Lennon and Yoko Ono, John Peel, Marty Feldman and a host of other celebrities rallied to the magazine’s cause. You’d be forgiven for thinking surely this was the last great clash of culture and state and that in these enlightened times, one is free to read and watch whatever one likes. After all, you can even see the raft of so-called ‘video-nasties’ that were for a number of years banned in this country. It may come as a surprise to many readers then to learn that the Obscene Publications Act was dusted off and wielded again, as recently as 1991 against David Britton’s novel, Lord Horror published by Savoy books. Lord Horror was the last book in the UK to be prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act. Copies of the book were seized (with some zeal at the hands of the then Chief Constable of Manchester Police James Anderton, the self-confessed God’s cop) and ordered destroyed. Britton was sentenced to four months in Strangeways.

It’s no easy thing to explain what Lord Horror is, but the novel follows the adventures of a bizarre Moorcockian manifestation of the British wartime radio traitor, William Joyce a.k.a. Lord Haw Haw. That said, the similarities between his real world progenitor and Britton’s creation are slight – both were powerful orators, accomplished brawlers and virulent anti-Semites, but there the likeness ends. Lord Horror is a straight razor wielding eviscerator, as happy debating philosophy and the merits of Fudge And Speck as he is disemboweling Jewesses and stringing their labia around his neck. Lord Horror is not for the weak of constitution, physically or mentally. Like The Naked Lunch, Lord Horror has no real discernible narrative and jumps through time and space with playful abandon, as happy to rewrite historical figures (in Lord Horror, James Joyce is Horror’s brother) as history itself. Anderton, and subsequently Magistrate Derrick Fairclough, main objection to the book was the horrifically violent and vocal antisemitism of its central character. Mind you, I’m sure part of Anderton’s ire came from his own thinly-veiled cameo as Chief Appleton. In on scene, Britton takes a speech Anderton once gave condemning gays and replaces each instance of the word gay with Jew. The irony was no doubt lost on Anderton.

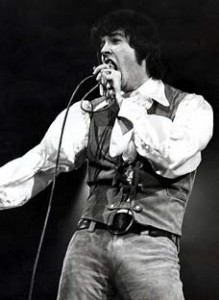

The ban on Lord Horror was repealed in 1992 after freedom group Article 19 successfully petitioned Geoffrey Robertson QC to have the conviction quashed. Undeterred, Britton (with his erstwhile editor Michel Butterworth) has written two subsequent Lord Horror titles: Motherfuckers – the Auschwitz of OZ, and Baptised in the blood of millions. The Lord Horror franchise isn’t just a literary one either, records, comics and art all contribute to the Lord Horror milieu. I myself am lucky enough to own a 12’’ copy of The Savoy Hitler Youth band’s Blue Monday. Copies of their Meng & Ecker comics are still banned, perhaps reflecting the lowly status of the comic as an art form. As for Lord Horror the novel, there are now only two ways you can get your hands on a copy (the book was never reprinted); an audio version of the novel on CD narrated by the fallen pop Lothario PJ Proby, and the other a Czech language edition. The wheel turns full circle.

The ban on Lord Horror was repealed in 1992 after freedom group Article 19 successfully petitioned Geoffrey Robertson QC to have the conviction quashed. Undeterred, Britton (with his erstwhile editor Michel Butterworth) has written two subsequent Lord Horror titles: Motherfuckers – the Auschwitz of OZ, and Baptised in the blood of millions. The Lord Horror franchise isn’t just a literary one either, records, comics and art all contribute to the Lord Horror milieu. I myself am lucky enough to own a 12’’ copy of The Savoy Hitler Youth band’s Blue Monday. Copies of their Meng & Ecker comics are still banned, perhaps reflecting the lowly status of the comic as an art form. As for Lord Horror the novel, there are now only two ways you can get your hands on a copy (the book was never reprinted); an audio version of the novel on CD narrated by the fallen pop Lothario PJ Proby, and the other a Czech language edition. The wheel turns full circle.

There’s alchemy at work. After being caught in a viscous downpour in Kutna Hora, Thomas and I drag ourselves, wounded and sodden back to the railway station. It’s with great relief that we sink back into our seats on the train bound for Prague. That is until the guard appears two stops later, frowns at out ticket and shakes his head. We’re on the train to Brno. Completely the wrong direction. We alight at the next stop, a small, typically rural Czech town called Caslav. A local helpfully informs us we have at least an hour to wait. We find a cosy looking pub and enjoy a pint. Thomas takes the opportunity to take some more pictures. Somewhat belatedly we’re back in Prague and I need to get my butt over to Theatre Minor as quickly as I can to cover the next event at the Writers’ Festival.

Before I head home on Friday evening, I have chance to take a quick dash around the tourist shops to buy some knickknacks for the folk back home. My stepfather has asked for Prague Hard Rock Cafe t-shirt (some folk are content to just collect badges) and my girlfriend wants a Golem. The t-shirt is easier to find, but the Golem, like the mythical beast itself, is a little more elusive. I have to traipse all the way over to the Jewish quarter to find my quarry.

The flight home is a short and painless two hours and gives me time to reflect on my week in Prague and the strange topsy-turvy times we’re living in. I contemplate synchronicity too, and the weft that holds the threads of politics, art and literature together. And just in case you don’t believe in synchronicity (in the Jungian sense at least), I got home to find my new copy of the Fortean Times lying on the mat. And guess what the cover article was? ‘The secret of the Golem – in search of Prague’s legendary monster.’ Alchemy indeed.

Stefan Pearson

Recent Comments